1

/

of

2

Mozart: 45 Symphonies

Mozart: 45 Symphonies

Regular price

$40.99 USD

Regular price

$53.99 USD

Sale price

$40.99 USD

Unit price

/

per

Shipping calculated at checkout.

Couldn't load pickup availability

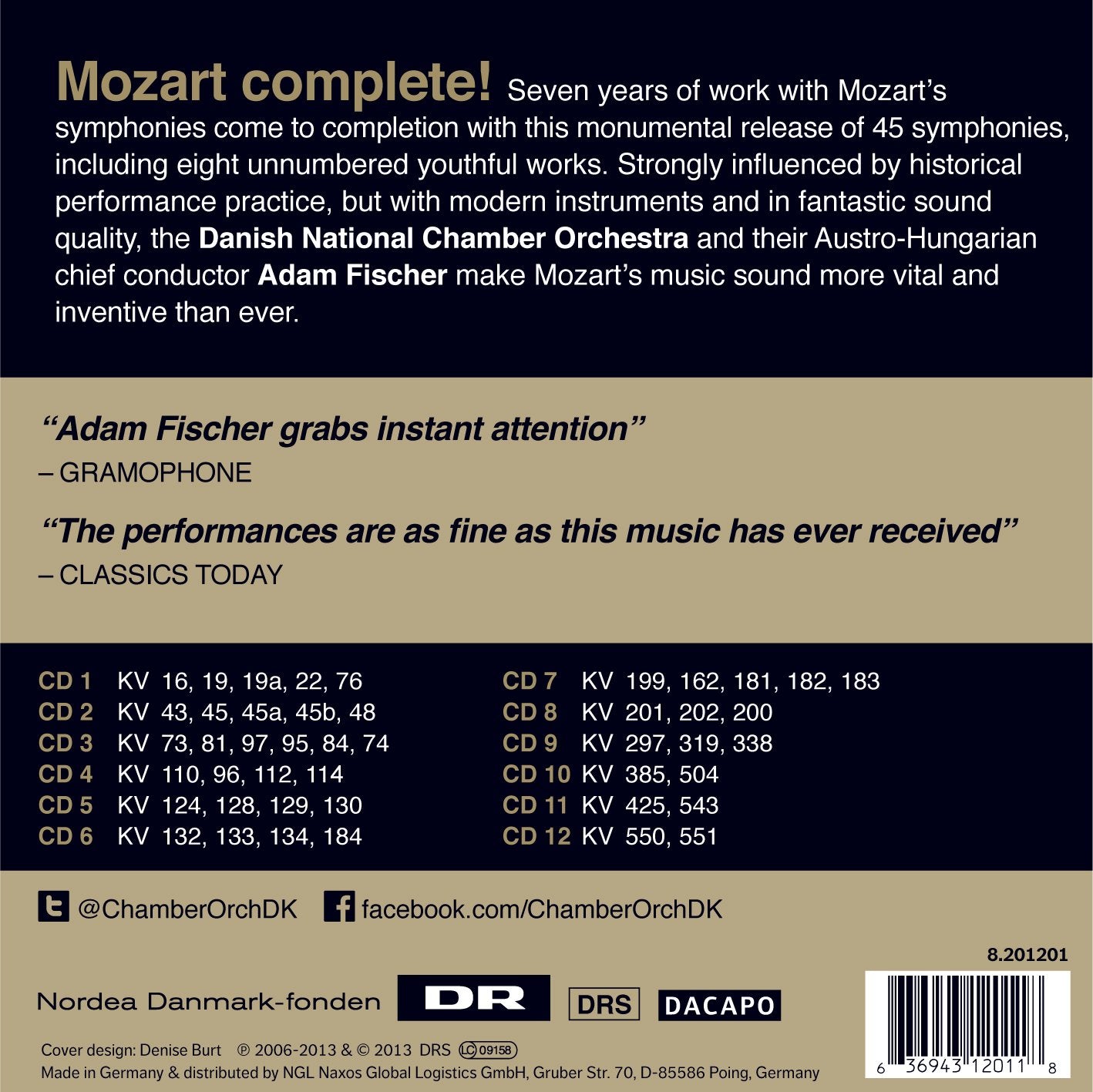

MOZART Symphonies Nos. 1, 4–31, 33–36, 39–41. Symphonies, K 19a, 42a, 45a–b, 73l–n, 73q, 111b • Ádám Fischer, cond; Danish Natl CO • DACAPO 8.201201 (12 CDs: 716:42)

I mentioned in my review of a single disc from this series, which included symphonies Nos. 28–30 (Fanfare 34:4), that I didn’t think that Ádám Fischer’s performances captured “Mozart’s drama as well as they capture his elegance,” but added the caveat that it’s difficult to gauge an entire series of symphonies by one CD. Alas, in later reviewing the disc including symphonies Nos. 31, 33, and 34, I had the opposite feeling, that Fischer was making a “race to the finish line” and playing the symphonies too quickly. Now, as it so happened, I reviewed those two discs about two years apart, and so did not have the first still on hand to compare to the second, or to think about the differences in approach. But now I have the full set of 45 symphonies to review, and my feelings have changed. Now I am inclined to agree with Patrick Rucker, who gave a rave review to the single disc of symphonies Nos. 15–18 in Fanfare 31:1 (a disc reviewed, I believe, before I joined the magazine staff), stating that he was “grasping for superlatives.”

The difference? Listening to the entire series in chronological sequence. By doing so, I noted that, despite an overall theatrical approach to these symphonies (in the liner notes, Fischer admits that he tends to think of orchestral music “operatically,” i.e., finding a dramatic theme or thread in the music that he then tries to bring out), he does make distinctions between the earlier and the later symphonies. Reducing his approach to a few basics, he plays the earlier symphonies with equal drama and electricity but with far fewer changes in dynamics and fewer rubato touches. In addition, I was able to download the scores of four of the symphonies—two of the most famous late works (40 and 41) and two early symphonies (Nos. 5 and 15, chosen pretty much at random)—and although these are not up-to-date, verified, Urtext scores like the ones Fischer worked from, they do include dynamics markings. And, as any number of conductors of the past have mentioned, they do not tell you what to do between the forte here and the piano four or six bars later (or vice versa). You are expected to follow your own good taste in approaching them.

Perhaps another deciding factor for me was in hearing Philippe Herreweghe’s more dynamic performances of symphonies Nos. 39 and 41 and, believe it or not, Bruno Walter’s historic performances of symphonies Nos. 39–41. Despite Walter’s slower tempos (and richer string sound), he actually elicited much more nuance and detail from those symphonies than did Jaap ter Linden, whose set I gave a good review to and suggested at the time that it was a fine historically-informed set of the Mozart symphonies. But, to be honest, what really sold me on Fischer’s approach were his performances of the early, lesser-known, oft-neglected, and unnumbered symphonies. Each and every one of them sounded as if it was just bursting with excitement, yet not too much that it overpowered the music on the printed page.

Moreover, what struck me in the single disc of symphonies 31, 33 and 34 as too fast now, suddenly, made sense in context. And, for the several Toscanini-bashers out there, I found it almost comical to note that Fischer takes the Finale of the “Jupiter” Symphony at virtually the same tempo that they consider “too fast.” The difference, of course, is that musicians of the 1940s and 50s weren’t used to playing Mozart this swiftly, and so they tended to sound pressed, whereas Fischer’s Danish National Chamber Orchestra skips through the music deftly and nimbly, like snow rabbits dashing across the landscape. It’s the comfort level of the executants that makes the difference, then, not the “wrong” tempo.

A good example of Fischer’s approach is CD 3, where he presents no less that four symphonies in a row that are all in the key of D Major (K 73l, m, n, and q). It would have been very easy for him, and the orchestra, to simply slip into an all-purpose style for these works, which of course would make them sound pretty much the same, yet he continually varies his approach from work to work. I do, however, caution the listener to approach this set one CD at a time. That is what I did, listening on consecutive nights to only one CD per evening, and it worked out pretty well. You get a better feel for the magnitude of Fischer’s achievement that way, and you are being fairer to both him and the Danish orchestra, whose players helped prod him on to take chances with the music and do things differently from the norm. After all, this was a seven-year project for them. These symphonies did not just get all rehearsed and recorded within a year or two.

I should also point out the work that went into Symphony No. 15, one of the four I obtained scores of. In the notes, Fischer asserts that if this work had not been by Mozart, who wrote so many symphonies and so many of good quality, it would probably be a much better known work, possibly a repertoire staple. Just reading the score, the music does look promising but certainly not brilliant. The first movement, for instance, is in a quick 3/4 time, featuring a jagged melody with the usual wide-ranging melodic leaps. From the first bar, the dynamics marking is forte, which changes to piano at bar 13, then back to forte at bar 22, piano again at bar 25, forte on the first beat of bar 30 with a sudden fp on the second beat (a half note played by the oboes, trumpets, and first violins, while the second violins play 16ths and the violas, cellos, and basses play eighth notes). It’s all pretty cut-and-dry, you might say, and this is how most conductors play it. Fischer adds a little burst of extra volume at the top of bar 5, when the agitated strings play against long-held notes by oboes and trumpets, and there are all sorts of little gradations of sound in various places, including slight crescendos to emphasize the musical drama. More interestingly, none of this sounds particularly fussy; if you didn’t have the score in front of you, or if you hadn’t heard any number of flat-response historically-informed performances, you’d think that this is simply the way the music goes. Toscanini once said it isn’t the f here or the p there that’s difficult to gauge, but what to do in between. Sadly, Toscanini paid little attention to most of Mozart’s symphonies because, except for the last three, he found most of them boring: “Is always beautiful, but always the same!” In Fischer’s performances, nothing is “always the same.” In the Andante of this Symphony, for instance, there are no dynamics markings at all, yet Fischer plays it at a moderate mp with further gradations down to p or pp and back again. By such means does he create and sustain interest.

The notes also explain the reason why the music sounds so vibrant and alive: His string players all use steel strings, which gives the music a consistently “edgy” quality that reveals, as Fischer put it, Mozart’s “earthily honest side.” The more you think about it, the more this makes sense, since Mozart was strongly influenced by both Haydn and C. P. E. Bach, both of whom exploited an earthy, dramatic quality in their symphonies.

Probably the most difficult aspect of the earlier symphonies to overcome was the monotony of orchestration. Clarinets, horns, and other instruments only begin to appear in Mozart’s symphonies later on; earlier, the composer had to rely on his ingenuity of counter-rhythms and occasional harmonic changes to sustain interest, and unlike Haydn, Mozart almost invariably sought the widest possible popularity for his music (perhaps one of the reasons why Toscanini found it “always the same”). Yet, as the notes also point out, in Mozart’s day no one bothered to listen to music more than three years old as a rule. It was all about what was new, not what had come before. No one gave a hoot back then about “historical performance practice” because they didn’t want it and wouldn’t have listened if you gave it to them.

I still feel that occasional movements, such as the Andantes of the “Paris” Symphony and No. 39, are a shade too fast for my taste, but in the context of Fischer’s overall musical conception what he plays works very well. I can now accept what I hear in those later symphonies because my tolerance was built up through what he did with the numerous early works. In short, I have taken this symphonic journey with Fischer, the only difference being that I did it in 12 nights rather than in seven years.

I have now replaced the Jaap ter Linden set of Mozart symphonies on my shelf with this one. I strongly urge you to give them a listen and see if you don’t agree.

FANFARE: Lynn René Bayley

Share

Product Description:

-

Release Date: January 28, 2014

-

UPC: 636943120118

-

Catalog Number: 8201201

-

Label: Dacapo Classical

-

Number of Discs: 12

-

Composer: MOZART, W.A.

-

Orchestra/Ensemble: Danish National Chamber Orchestra

-

Performer: Fischer